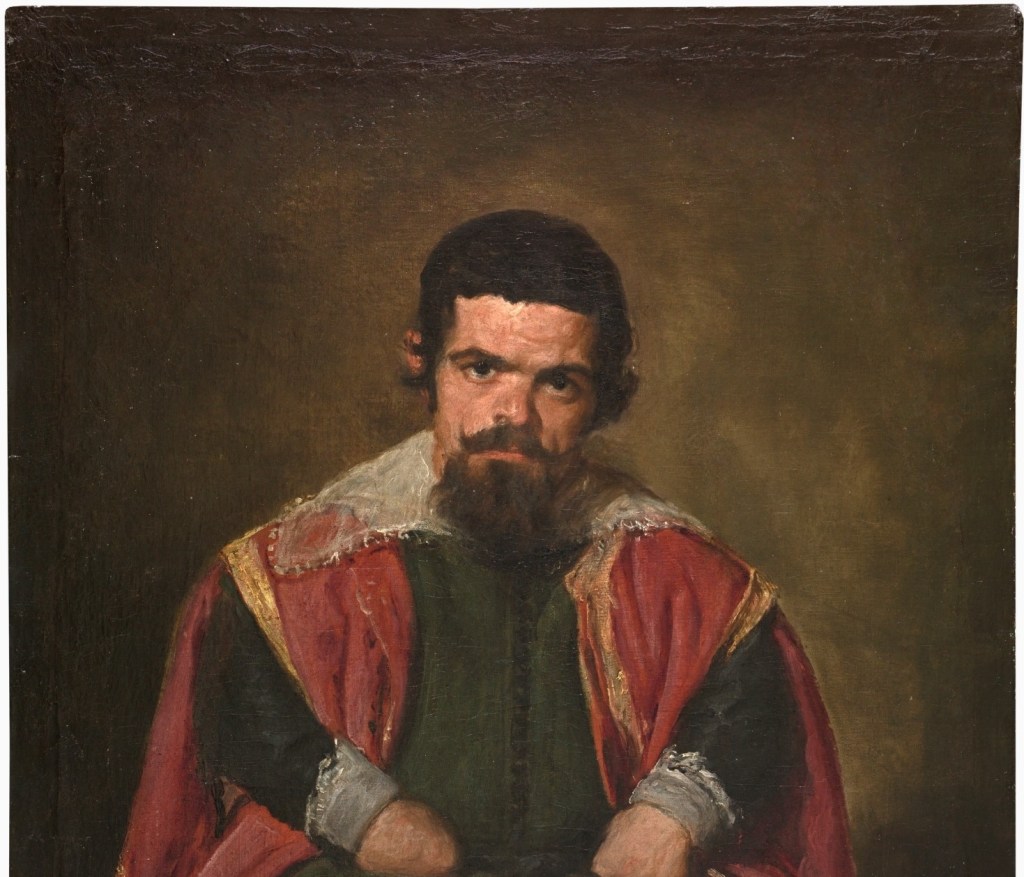

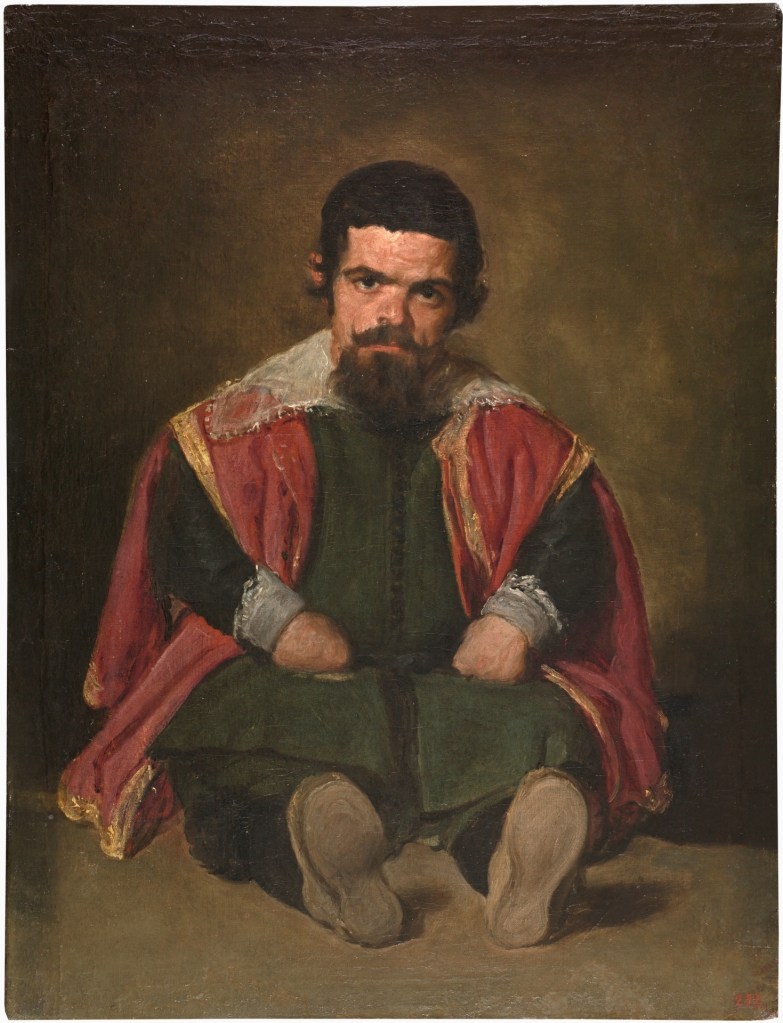

The first thing one notices are the eyes. They peer at the viewer with an audacity bordering on insolence. They say plainly that the soul behind those eyes is the equal of any viewer. In fact, in their somewhat intolerant way, they suggest that he may be the viewer’s superior.

Only when the viewer backs up and sees the portrait in whole, does he notice that Sebastián de Morra, the artist’s subject, is a dwarf.

Dwarfs, or “little persons” as some prefer to be called, were in the news last year, thanks to the controversy over Disney’s Snow White. Actor Peter Dinklage, who has a form of dwarfism called achondroplasia, denounced Disney for its plans to make “that fucking backward story of seven dwarves living in the cave.” Immediately following his criticism, a number of high profile writers and activists piled on, supporting his outrage.

That was enough for Disney. It bent its corporate knee with the kind of craven apology typical in such situations, announcing:

To avoid reinforcing stereotypes from the original animated film, we are taking a different approach with these seven characters and have been consulting with members of the dwarfism community. We look forward to sharing more as the film heads into production after a lengthy development period.

The Company replaced the dwarfs with computer generated images.

Disney’s timidity did not help its bottom line. Snow White was a box office disaster. Moreover, by deferring to Dinklage and eliminating the dwarf roles, as Reason Magazine’s critic noted, “Disney hurt the very people they were supposedly protecting.”

If one wants to see an example of real courage in the treatment of dwarfs, don’t bother listening to Dinklage or watching Disney. Instead, travel back four centuries to Imperial Spain, and witness the works of Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez. His respectful portrait of Sebastián de Morra was a true profile in courage, To fully understand this, one must consider the attitudes of the age.

In a period popularly known as “the Enlightenment,” the treatment of dwarfs was anything but. Dwarfs were employed as court entertainers and were treated more like possessions than people. They were frequently “gifted” from one noble’s house to another. De Morra himself was employed as a court dwarf for King Phillip IV of Spain, who had received him as a gift from his younger brother Cardinal Infante Fernando. The King later passed him on to Prince Baltasar Carlos.

The dwarf’s job was to amuse. Their small stature was seen as comical. Viewers assumed that their intellect was similarly stunted. Ironically, owing to that assumption, dwarfs were given latitude to speak freely. Criticism, even criticism of their royal masters, was tolerated. Coming from a dwarf, such comments were considered funny and thus permissible.

Peter the Great, Tsar of all Russia, was considered the leading reformer of his age. He was the man who brought Western science and culture to a backward, theocratic Russia. Before his reign, a total of 500 books had been published in his homeland, most of them ecclesiastical. During his reign, 1,200 were printed, most of them secular.

How did this so-called reformer treat dwarfs?

The Tsar, at six feet seven inches, was obsessed with little people, and maintained a retinue of them at court. In preparation for the wedding of his niece Anna to Frederick William, the Duke of Courland, Peter ordered that all the dwarfs of Moscow be rounded up and shipped to St. Petersburg, where they were kept penned up like cattle. During the royal nuptials, Peter produced a mock wedding for the amusement of his guests. A procession of 72 dwarfs paraded to the cathedral, where a fake ceremony was held. After the ceremony, the dwarfs were led to the Palace, where they had their own pretend feast. Plied with food and vodka, the dwarfs ate, drank, and danced. As most were unaccustomed to liquor, the event soon deteriorated into a drunken brawl, to the delighted amusement of the royal guests seated around them.

On other occasions, Peter entertained his dinner guests by having a naked dwarf jump out of an enormous pie.

The treatment of dwarfs in Western Europe was equally inhumane. Jeffrey Hudson, an English dwarf of the same time period, was also trained to leap out of a giant pie for the amusement of the guests of the Duchess of Buckingham. But he did not leap naked. Instead, he was attired in a tiny, specially crafted knight’s armor. Among the guests was the Queen, who was so impressed by the farce that she brought Hudson back to London, where she housed him with her pet monkey.

This is what makes the works of Velázquez so notable and noble. In a world where dwarfs were objects to be snickered over and sneered at, to be caged like pets, then gifted away to others, this artist saw in their faces their essential humanity, and he reflected that humanity in his art. Other artists of his time also painted dwarfs. But in their works, the dwarfs appear not separately, but next to the main subject, typically their owner. The dwarfs serve as accessories, emphasizing the owner’s power and wealth, as we see in Rodrigo de Villandrandro’s painting of Prince Phillip towering above Miguel Soplillo. Velázquez, an iconoclast, painted dwarfs as individual subjects, and imbued them with individual dignity.

This is not to say that the man was a saint. A serial philanderer, Velázquez engaged in extramarital affairs, including one with an Italian model name Jeronima Montanes, who bore him an illegitimate son.

In addition to his role as royal painter, Velázquez was also responsible for managing the purchase of palace art. He was a poor record keeper, and after his death, his estate was sued for embezzlement. His son-in-law, who had inherited his position as royal painter and his liabilities, was compelled to pay a fine of 16,000 ducats. (At current gold prices, that would amount to several million dollars.)

But when his hand touched a brush – rather than a woman or a till – an elevated sentiment guided him, inspiring him to create masterpieces, not just of art, but of humanity. Thanks to Velázquez, we see the dwarfs of his age as real human beings, rather than foils or fools.

In our own age, it is common to bandy about phrases like “speaking truth to power,” and “joining the resistance.” But those purporting to speak truth to power often have more power than those they speak to, and those claiming to resist often do so from the safety of the herd.

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez was born more than four centuries ago. But his treatment of little people teaches us what it is to be a modernist today.