When Samuel Clemens, better known by his pen name Mark Twain, died in 1910, the New York Times deemed him the greatest humorist and satirist in the English-speaking world. William Faulkner later went beyond that accolade, and called him “the father of American literature.”

There is another lesser known area in which superlatives are due. He was the most fervid and imaginative champion of copyright law this country has ever produced.

In his magisterial biography, Ron Chernow characterizes Twain’s attitude toward copyright law as “militant.” Chernow likes the adjective so much that he uses it three times. And it is proper to do so. For while all writers wish to maximize their copyright protection, none have been as combative as Twain in attempting to stretch the boundaries of that legal doctrine.

For most of his life, his attempts failed. But he never gave up. In the end, he succeeded.

Twain’s first attempt at expanding copyright protection came about in 1894 when he found himself teetering on the brink of bankruptcy. Twain was an inveterate sucker for get rich schemes. His wife, Olivia (Livy) Langdon, was the daughter of a wealthy coal magnate and her resources permitted him to indulge that weakness. Twain frittered away most of Livy’s inheritance on expensive, ill-considered ventures. One was a typesetter invention which was supposed to revolutionize printing but which never worked properly. Another was a publishing house that produced one bestseller (Grant’s autobiography), followed by a string of losers (including a collection of sermons, 75 recipes for cooking eggs, and an analysis of the speech of monkeys).

As his financial picture darkened, Twain feared that his creditors would seize his most valuable asset: the copyrights to his literary works. Following the advice of Henry H. Rogers, a Standard Oil mogul, Twain assigned his copyrights to his wife. Then he filed for personal bankruptcy.

This was a gambit of questionable legality and ethics. If tried today, such assignments would likely be cancelled as fraudulent conveyances, and the copyrights would be subject to attachment by creditors. Fortunately for Twain, his attempt was never tested. His creditors offered to relinquish their claims in return for payment of 50 cents on the dollar. Twain paid half of that amount up front. He promised to pay off his debts in their entirety – 100 cents on the dollar — over time. His creditors allowed him the opportunity.

Twain’s offer was not entirely voluntary. His wife Livy considered bankruptcy a “disgrace.” She was willing to turn over the family house, including its land and furniture, to her husband’s creditors to avoid such infamy. For the sake of domestic tranquility, Twain had little choice but to make good on his promise.

Twain embarked on an extensive and exhausting speaking world tour, which generated enough revenue for him to pay off his creditors in full, thereby placating Livy, and leaving his copyrights untouched.

Though safe from creditors, Twain realized that his copyrights were vulnerable to time. The existing copyright act provided for a term of protection of 28 years, plus a renewal of 14, for a total of 42 years. As he aged, Twain worried that he would have no literary rights to bequeath to his wife and children.

In 1906, Twain experienced what his biographer Ron Chernow describes as a “brainstorm.” He would work on an autobiography. Whenever one of his books approached the end of its copyright term, Twain would inject footnotes made up of passages from his autobiography into it. This, he thought, would create a whole new work entitled to a whole new copyright term.

Twain was very proud of this “brainstorm,” and boasted about it to the press. A New York Times reporter reflected that enthusiasm as he described Twain’s innovation:

Mark Twain has the copyright law beaten to a frazzle…. He has a scheme which puts his children beyond the reach of want till they shall be old ladies and makes the present copyright law look like a very sick and discomfited pirate, indeed.

Mark Twain looks upon the copyright law as pure robbery…. For years Mark Twain has devoted his intellect to the question how to beat this law, how to foil this robbery, how to insure to his children the profit of their father’s labor, and prevent it from being handed over by the Government to some publishers who have never done anything for Mark….

The weapon whereby Mark Twain has vanquished the copyright law is his much heralded autobiography….

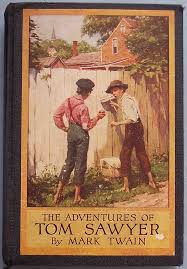

As soon as the copyright expires on one of his books Mark Twain or his executors will apply for a new copyright on the book, with a portion of the autobiography run as a footnote. For example, when the copyright on “Tom Sawyer” expires, a new edition of that book will be published. On each page a rule will be run about two-thirds of the way down the page, and below these lines will be printed the autobiography, or so much of it as is designed for publication in that volume.

Twain somehow got the idea that injecting new material into a moribund copyright was comparable to injecting a blood transfusion into a gravely ill patient. The injection would miraculously save the patient and make him young again. Or at least young enough to benefit from a second copyright, thus lengthening the term of copyright protection from 42 to 84 years.

That is not how copyright worked then and it is not how it works now. Adding new material results in a new copyright all right – but only for the new material, not for the preexisting literary work to which the new material is appended. In the hypothetical example used by the New York Times reporter, when the copyright on “Tom Sawyer” expired, any publisher would be free to print its own edition of the classic work. It just couldn’t include the new autobiographical footnotes.

Twain’s next idea for extending copyright protection was generated not by him, but by Ralph Ashcroft, a dodgy fellow who managed to worm his way into Twain’s confidence. Ashcroft convinced Twain that by registering his pen name as a trademark, he could enjoin publishers from printing unauthorized copies of his books even after their copyrights had expired. In 1908, at Ashcroft’s behest, Twain registered his pen name as a trademark, then set up the Mark Twain Company to own it.

Twain deemed this strategy “a stroke of genius,” and predicted that it might “supersede copyright law someday.” He beamed as Ashcroft told the press: “Mr. Clemens’s heirs will be in a position to enjoin perpetually the publication of all of the Mark Twain books not authorized by the Mark Twain Company.” A grateful Twain made Ashcroft a director of the Mark Twain Company, entitling him to a percentage of royalties earned from his books. He even signed a power of attorney, giving Ashcroft virtually complete power over his financial affairs.

When his daughter Clara questioned Ashcroft’s integrity, Twain assured her that “his services have been absolutely endless.”

Ashcroft’s services might indeed have been “endless,” but only in the sense that he endlessly sought ways to profit from the relationship. With the power of attorney, Ashcroft bragged that his control over Twain’s finances was so great, “I can sell his house, over his head, for a thousand dollars, whenever I want to.” He married (and later divorced) Isabel Lyon, Twain’s household manager and secretary, and the two set about embezzling. When Twain found out and confronted them, they fled the country.

Like Twain’s notion of creating a perpetual copyright by injecting new autobiographical material into old works, Ashcroft’s notion of achieving the same goal by registering Twain’s pen name as a trademark was a delusion. It rested on a misunderstanding of the relationship between copyright and trademark law.

The function of trademark law is to enable consumers to determine the source of products, and to protect them from confusion. The purpose of copyright law is to grant authors the “exclusive right” to their writings “for limited times.” The quoted language is from Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution. Once the limited time expires, the writings lose their copyright protection and enter the public domain.

An author’s name can indeed function as a trademark, if the author has produced (or licensed others to produce) non-literary products marketed under that name. So Mark Twain could have used his trademark to prevent others from making and marketing unauthorized MARK TWAIN cigars, suits, or sweatshirts. Considering his status as a global celebrity, using trademark law to prevent such abuses of his name made sense. But he could not prevent others from publishing new editions of his works that had entered the public domain, even if those new editions bore his name. A publisher was free to cite his name as the author of, for example, a new edition of “Tom Sawyer” because such use would be truthful. There would be no public confusion because Mark Twain really was the author of “Tom Sawyer.”

Ashcroft’s idea couldn’t work because it would violate the Constitution by rendering its reference to “limited times” nugatory. Trademark law, which is a creature of statute or common law, cannot trump the Constitution, which is the supreme law of the land.

Twain probably should have realized that Ashcroft’s notion had no chance of success. Years earlier, Twain himself had lost a lawsuit in Chicago, arguing much the same theory; namely, that his pen name should entitle him to prevent the marketing of pirated copies of his works even if those works were not copyrighted. A century later, Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for a unanimous Supreme Court in the case of Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., would formally reject the idea of using trademark law to prevent the copying of works in the public domain as an attempt to create “a species of mutant copyright.” Neither Twain nor Ashcroft could ever sire such mutants.

Despite his many missteps, Mark Twain eventually accomplished his goal of expanding copyright protection. On March 4, 1909, on his last day in office, President Theodore Roosevelt signed into law the Copyright Act of 1909. Twain had lobbied the President and Congress to support such a bill, camping out at the Willard Hotel and meeting with with legislators who were only too happy to be seen associating with such a celebrity. In fact, the final bill signed by Roosevelt was even more generous than the version for which Twain had lobbied. Twain’s favored bill had provided 50 years of copyright protection. The 1909 Act granted authors 56 years of protection (a 28-year term, and an additional 28-year renewal).

A year after President Roosevelt signed the Act, Mark Twain died, his copyrights intact. Sadly, his main reason for championing expanded copyright protection – to protect his family — had lost most of its impetus. Twain outlived his wife Livy, and 3 of their 4 children. Clara, his one surviving child, was financially comfortable, having married Ossip Gabrilowitsch, a world-renowned Russian pianist who later became the conductor of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra.

But regardless of their purpose, and regardless of their meanderings and eccentricities, Mark Twain’s adventures in copyright protection were noble. Generations of subsequent creators could thank him for his efforts, just as millions of readers have thanked and continue to thank him for a life well spent making the world laugh.

Who uses nugatory?

Those who eschew otiose.