The political weather forecasts call for balmy weather for Democrats. According to RealClearPolitics, which aggregates and analyzes a number of polls, President Trump’s approval ratings crossed into negative territory in March 2025 and have been trending steadily more negative ever since. They now stand at 55.5% negative to 42.0% positive.

Democrats are optimistic about the upcoming midterm congressional elections. They need a net gain of only three seats to take control of the House of Representatives, and they expect to easily surpass that number. Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee Chair Suzan DelBene (D-Wash.) claims that 44 Republican-held seats are in play. James Carville predicts that Republicans will suffer a “wipeout,” with Democrats picking up somewhere between 25 to 45 House seats, and taking control of the Senate.

History supports Democratic optimism. The party in the White House usually fares poorly in midterm elections, losing congressional seats 20 of the last 22 times. The losses are particularly bad in the midterm elections of the President’s second term, a phenomenon known as “the sixth year itch.” Trump is in his second term.

So Democrats should be completely cheerful, right? Not quite. In fact, despite the sunny near-term prospects, there are storm clouds just beyond the horizon.

On January 27, the U.S. Census Bureau released population estimates for all 50 states. The data has political implications because a state’s population determines its number of votes in the Electoral College. Each state is accorded a number of electoral votes equal to its number of its House seats, plus two more for its Senate seats.

There are 435 House seats, apportioned every ten years among the states. A state’s share of House seats is based on its population. States with populations growing at a higher rate than the national average get more House seats and thus more electoral votes after the census. States with populations that are contacting, or growing at a lower rate than the national average, receive fewer House seats and thus fewer electoral votes.

For 48 states, it’s winner-takes-all in the Electoral College. The winner of the state’s popular vote receives all of its electoral votes. The two exceptions, Maine and Nebraska, award one electoral vote to the winner of each congressional district, and two electoral votes to the statewide winner. Under the Twenty-Third Amendment, the District of Columbia is accorded no more than the least populous state, meaning three electoral votes. Adding up the 435 House seats, the 100 Senate seats, and the 3 D.C. votes, produces a total of 538. To win a presidential election, a candidate must receive a majority of those 538 electoral votes, meaning a minimum of 270.

Redistricting experts immediately seized on the U.S. Census Bureau population numbers to see how the population trends might affect the 2030 reapportionment and thus the makeup of the Electoral College. Geoffrey Skelley of Decision HQ has analyzed their projections and found that, despite some methodological differences, all the experts foresee trouble for future Democratic presidential hopefuls.

The blue states where Democrats traditionally garner their electoral votes are losing population relative to the rest of the country. The red states where Republicans garner their electoral votes are gaining population relatively. If the trends continue to 2030 when the decennial census takes place, it will become increasingly difficult for Democrats to amass the 270 electoral votes needed to win the presidency, and increasingly easy for the Republicans to do so.

The reliably red state of Texas will gain four electoral votes, and Florida three. North Carolina, Idaho, and Utah, which also usually vote red, are on course to gain one electoral vote apiece.

On the other side of the ledger, the reliably blue state of California will lose four electoral votes and New York will lose two. Other usually blue states – Illinois, Minnesota, Oregon, and Rhode Island – are each projected to lose a seat.

Georgia and Arizona are each likely to gain one vote, while Pennsylvania and Wisconsin are each projected to lose one. Given their nature as swing states, it is impossible to predict how their population growth or contraction will affect Electoral College outcomes.

Overall, these population shifts signal serious danger for Democrats.

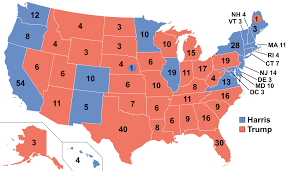

Imagine a rematch of the Trump vs. Harris campaign waged against the backdrop of a post-2030 electoral map. In 2024, Trump defeated Harris 312 to 226 in the Electoral College. If both candidates received the same number of popular votes distributed in the same states, Trump’s electoral vote tally would swell by 10 and Harris’s would decline by the same number. As Geoffrey Skelley points out, the effect of these demographic trends would be the same as taking a medium sized blue state and moving it from the Democrats’ column to the GOP’s.

The population shift could also affect campaign strategy. In the last three presidential elections, much attention was lavished on the so-called “Blue Wall” battleground states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. They were viewed as crucial to victory — and with good reason. Trump won all three states in 2016 and 2024, and won the election. He lost all three states in 2020, and lost the election. But if the projected population shifts actually occur, the Blue Wall states may lose their status as vital electoral masonry. For under those shifts, a Democratic presidential candidate who won every state carried by Kamala Harris, plus all three Blue Wall states, would still lose. That candidate would garner only 258 electoral votes, well short of the 270 needed to win.

Of course, these are merely trends, not certainties. Some storm clouds pass without dropping rain, and there are reasons that might happen here.

The experts projecting a coming Republican electoral advantage may be wrong. Experts often are. In 1969, a political expert named Kevin Phillips surveyed Richard Nixon’s election victory and wrote a bestseller titled The Emerging Republican Majority. Phillips foresaw a generation of Republican presidential election victories. What he didn’t foresee was Watergate. In 2002, John Judis and Ruy Teixeira surveyed the nation’s demographic changes, and wrote a book titled The Emerging Democratic Majority. They predicted that the growing number of professionals, minorities, and women voters would ensure Democratic dominance. What they didn’t foresee was Donald Trump, and the movement of traditional Democratic voters to the Republican side.

In addition, under the 14th Amendment, reapportionment is based on the “whole number of persons in each state.” Immigrants, legal or not, are included in the count. The Trump administration has effectively closed the border. But changes by a different administration before the 2030 census might lead to an influx of immigrants to blue states, neutralizing the currently predicted population increases in red states.

And even if the population shifts seen in the U.S. Census Bureau report materialize, there is no guarantee that such shifts will result in an Electoral College GOP advantage. Democrats moving from California or New York, to Texas or Florida, may turn those red states blue, or at least purple. Texas and Florida were once reliably Democratic states. They could be again.

Finally, other currently unexpected demographic trends could emerge to complicate the picture.

In 1930, no one would have predicted that roughly 2.5 million people would leave the Plains States of Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri, and Texas due to drought conditions, with many of them ending up in California. Trends can lead to counter-trends. Beginning in 1910, about 6 million black Americans left the rural South for the northern industrial centers of New York, Chicago, and Detroit, to escape Jim Crow laws and racial violence and to seek economic opportunity. This was known as the Great Migration. Beginning in 1970, in what has become known as the New Great Migration, a steady stream of black Americans have reversed that trend, moving away from the Northern cities, back to the Southern cities of Atlanta, Charlotte, and Dallas.

To gauge the possible impact of the current population movement away from blue states toward red states, one must do more than just observe it. One must figure out why it is happening.

People are not neatly categorized. They pick up and move for different reasons. But if one compares the states gaining population with those losing population the most salient and recurring difference seems to be taxes. The blue states of New York and California have the highest income tax rates in the nation. Texas and Florida are among the seven states that do not have income taxes. Most of the other states without income taxes — Alaska, Nevada, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Wyoming – also usually vote Republican.

This suggests that the American demographic changes represent an election of sorts. Americans are examining their pocketbooks and then voting with their feet. With the right party platform changes, those same feet could point them in a different direction.

The Democratic Party – like its Republican adversary – exists for one purpose: to win elections. If it does its job properly, it will not let giddiness over its expected midterm victories this November blind it to the longer term dangers lurking in the U.S. Census Bureau figures. Instead, it will look at those dangers with candor, and then adjust its platform to counter them.