Is the nation facing a constitutional crisis?

“Sure are!” say any number of pundits. According to Adam Liptak of the New York Times, the question is not whether such a crisis exists, but rather how that crisis “will transform the nation.” Presumably, badly. And to his colleague Jamelle Bouie, the actions of President Trump are not just “unconstitutional,” they are “anti-constitutional,” because they “reject the basic premise of constitutionalism.” In other words, asking whether Trump’s actions are merely unconstitutional should trigger the response: “We should only be so lucky.”

The truth is less dramatic. We are not facing a constitutional “crisis.” Rather, we are seeing exactly the kind of inter-branch conflict our Constitution was designed to foster.

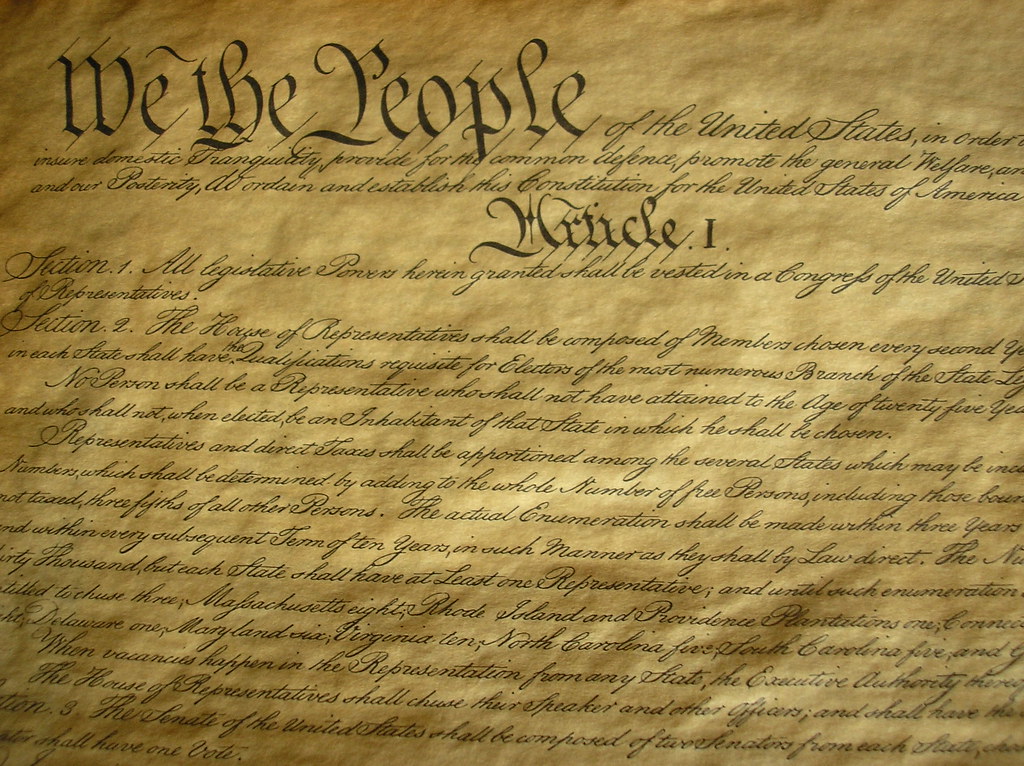

The level of discourse about a possible constitutional crisis would benefit if those wishing to opine were first required to read the Constitution. Not just the first ten amendments, commonly known as the Bill of Rights. The actual original un-amended document ratified in 1788.

That document is an architectural blueprint of the nascent federal government. The defining feature of the new structure is perpetual tension. Each of the three branches is designed to press against the other two. This state of constant stress is popularly known as our system of “checks and balances.” “If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” observed James Madison in Federalist No. 51. Since they are not, the Framers designed a system of checks and balances as the best preventative against mankind’s timeless tendency to amass power:

…[T]he great security against a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department, consists in giving to those who administer each department the necessary constitutional means and personal motives to resist encroachments of the others. …. Ambition must be made to counteract ambition.

Having the three branches engage in ceaseless bickering over their respective spheres is not a design flaw. It is the whole point.

The Constitution created the Supreme Court, but under our system of checks and balances, Congress checks the judiciary by holding the power to create the subordinate courts. The President checks the courts by holding the power to nominate the men and women who sit on them. Congress checks the President by making his selections subject to its “advice and consent.” The Senate checks both by exercising the power to try judges (and the President) in cases of impeachment. For its part, the judiciary checks the other two branches by rejecting laws found to violate the Constitution.

If this seems novel, it is only because few people tend to read the Constitution nowadays. Instead, commentators focus on the first ten amendments, known as the Bill of Rights. These amendments enumerate important individual rights which the government is required to protect. But the basic Constitution, with its system of checks and balances, plays the more vital role.

Many countries have lofty eloquent bills of rights, yet they are ruled by authoritarian governments. For without a system of restrictions on the government, a bill of rights is merely a worthless piece of paper. The United States has both, but, as the late Justice Scalia observed, if forced to choose, we would be better off having our Constitution without a Bill of Rights, than having a Bill of Rights without our Constitution.

So when hearing cries of “constitutional crisis,” we should remember that the three branches are not designed to co-exist peacefully. They are designed to conflict, as they check and balance each other.

When President Trump calls for the impeachment of Judge Boasberg because he dislikes the way he is presiding over the case of the alleged Venezuelan gang members, Trump is behaving intemperately (what else is new?) but he is hardly engendering a constitutional crisis.

The power to impeach federal judges resides in the legislative branch, not the executive, and it requires a 2/3 vote of the Senate to remove one. The odds of mustering the 67 votes in the Senate needed to remove Judge Boasberg are zero.

It is not even clear what Trump means when he calls for the Judge’s impeachment. Trump himself has been the object of many impeachment attempts, and for the most part they have been pure stagecraft. The first efforts to impeach him were made in January 2017 before he was even sworn in for his first term. Six months later, formal articles of impeachment were filed by Texas Congressman Al Green (the same cane-wielding Congressman ejected from the House chamber for interrupting Trump’s March 4 address to a Joint Session of Congress). We are barely into Trump’s second term, and already 250,000 people have signed a petition calling for his impeachment. And all of these efforts are separate from the formal impeachment proceedings held in Congress in February 2020 and January 2021.

All of which is to say that when Trump refers to “impeaching” Judge Boasberg, he likely uses the term in the same loose way his enemies use it against him; namely, to signify intense dislike. Actual removal is not even a remote possibility.

Following Trump’s call for Judge Boasberg’s impeachment, Chief Justice John Roberts issued a public statement, reminding the President that the appellate process, not impeachment, is the settled method for responding to an unfavorable judicial decision. The Chief Justice’s statement caused considerable pearl-clutching, with commentators describing it as “rare,” “unusual”, and “almost unprecedented,” thus contributing further to the sense that we are facing a constitutional crisis.

But the back and forth between the President and the Chief Justice was consistent with their respective roles in the constitutional system of checks and balances.

The fact that we are not facing a constitutional “crisis” does not mean there is no cause for concern. There is such cause, and its existence stems from the nature of the judicial branch.

Conflicts between the executive and legislative branches are normal, even healthy. Both branches are answerable to the voters, and therefore are deterred from adopting extremist measures. Moreover, both branches are constitutionally equipped with weapons to use in such conflicts. Congress has the power of the purse to support its policy decisions. The President has command of the federal law enforcement agencies and the armed forces.

Compared to the legislative and executive branches, the judicial branch is weak. It has no budget, other than what Congress grants it. It has no army. It has no police force, other than courtroom marshals and bailiffs. That is why Alexander Hamilton, writing in Federalist No. 78, referred to it as “the least dangerous” branch.

The power of the judicial branch comes from its prestige. Its orders command respect and obedience because judges are viewed as having exalted status, above that of ordinary elected political officials. That is why they have lifetime appointments and sit on elevated benches and wear black robes.

But prestige is an uncertain commodity. Prudent judges will use it cautiously. Chief Justice Marshall, generally considered one of our greatest and strongest judicial officials, set an example.

In Marbury v. Madison, he first articulated the Supreme Court’s power of judicial review. This power makes the judicial branch co-equal with the legislative and executive branches, as it allows it to invalidate any measures found by the Court to violate the Constitution. But Marshall reached this decision in a clever way.

The issue in the case involved the right of William Marbury to receive a commission, signed by the outgoing Federalist Party President John Adams, to be a justice of the peace. The incoming President Thomas Jefferson, a member of the opposing Democratic-Republican Party, refused to allow his Secretary of State James Madison to deliver the commission. Marbury filed suit in the Supreme Court, demanding that it issue a writ of mandamus, compelling Madison to deliver his commission. Marbury based his suit on the Judiciary Act of 1789, under which Congress gave the Supreme Court original jurisdiction to issue such writs.

Chief Justice Marshall was a Federalist. A partisan judge might have demanded that Jefferson’s administration deliver Marbury’s commission to him. Had he done so, Jefferson would probably have ignored him, and a true constitutional crisis would have arisen. Instead, Chief Justice Marshall ruled against Marbury, holding that the Act passed by Congress was unconstitutional because the Court’s original jurisdiction was prescribed by the Constitution. Any legislative act purporting to alter or expand that jurisdiction violated the Constitution, and was therefore void.

And so, in a nimble feat of judicial engineering, Chief Justice Marshall articulated a major Supreme Court power (judicial review) by disclaiming a relatively minor one (original jurisdiction to issue writs of mandamus).

The Supreme Court would not exercise its power of judicial review again for another 50 years. (It did so in the Dred Scott case, a decision widely considered the worst in the Court’s history, and which was reversed by the 13th and 14th Amendments.)

Chief Justice Roberts is known to be a great admirer of Marshall. Many commentators have compared Roberts’s opinion upholding the Affordable Care Act to Marshall’s opinion in Marbury. Both decisions were based on careful analyses of the respective powers of the branches of government, and both forestalled confrontations with the then current administration.

Should the Supreme Court issue an opinion today contravening an action of the Trump Administration, and should Trump go beyond gripes and verbal invective to outright disobedience, we would then face a true constitutional crisis. But President Trump, even in his most intemperate statements, has never claimed the right to disobey a Supreme Court ruling. And Chief Justice Roberts seems profoundly averse to creating a situation where Trump might be tempted to try to do so.

We are not facing a constitutional crisis today. And as long as Chief Justice Roberts and President Trump wish to avoid one, we will not face a constitutional crisis in the future.